Forensic Architecture: Eyal Weizman, Paulo Tavares, Samaneh Moafi, Christina Varvia, Nabil Ahmed, Sophie Springer, Lorenzo Pezzani, Jason Men

m7red: Mauricio Corbalan, Pio Torroja

In collaboration with FIBGAR: Baltasar Garzon and Manuel Vergaras

Co-curated with: Anselm Franke

A Natural History of Human Rights – 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial – Are We Human?

Una ecología política de las personas no humanas.

Casi en tiempo real, a través

La selva de Borneo y Sumatra

A miles de kilómetros de allí,

Este hito en la controversia por la tutela

En el caso Sandra confluyen las figuras del orang-utan un animal considerado el umbral entre el humano y

The Cloud

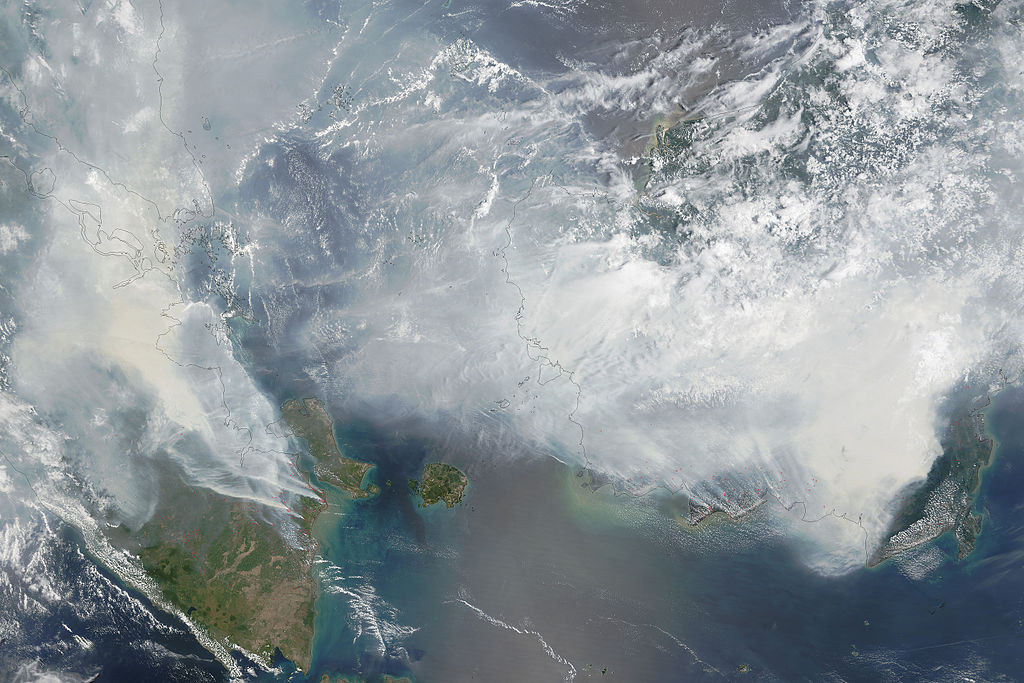

In 2015, fires in the Indonesian territories of Kalimantan and Sumatra, consumed over 21,000 square kilometers of forest and peat lands. Fumes from about 130,000 local sources combined into a massive cloud, a few hundred kilometers long and a few kilometres thick. It contained more carbon, methane, ammonium and cyanide than those produced by the entire annual emissions of the German, British or the Japanese industries. As the acrid cloud drifted north and westwards it engulfed a zone that extended from Indonesia to Malaysia, Singapore, southern Thailand and Vietnam. Scientists predicted more than 100,000 premature deaths and that the fires might push the world beyond 2C of warming and well into the unpredictable calamities zone faster than expected.

Weaponizing the Climate

Commentators referred to this cloud as “the greatest environmental disaster of the 21st century,” and international lawyers such as Baltasar Garzón as the harbinger of a new international crime of ecocide, one likely to become more relevant in the years to come. Garzón’s foundation FIBGAR commissioned Forensic Architecture to gather evidence for the causes and consequence of forest fires in Indonesia with the aim of an international trial in a number of states worldwide. We were also asked to participate in the development of political and legal vocabulary to address the relation between human and environmental violence. Unlike war, political repression, violations of human rights, crimes against humanity and genocide—ecocide is an indirect form of violence, its consequences are diffused and distributed in time and space, the causal structures it relies upon is nor linear and proximate but one resembling a field of forces.

Orang-utan Rights

An incidental casualty of the fires are the indigenous orang-utans, creatures that for centuries inhabited the aforementioned threshold between man and nature. Following the excessive forest fires in the past two decades, the number of orang-utan remaining in Borneo and Sumatra has decreased by 20,000. While in the 18th century the proximity between the species was based on ape’s physical resemblance to humans today it is neurological, genetic, social and linguistic similarities that are at the frontiers of debates regarding the future of laws and rights pertaining to them. Are apes objects or subjects of law? Should the killing of orang-utans be considered as a murder? Is the looming extinction of this specie a result of genocide or ecocide?

The Sandra Case

In 2014, after a long legal process brought up by AFADA, an animal rights association, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Sandra, a German born (Rostock Zoo) 30 year old female orang-utan has won a legal status resembling human rights. After many rejections, the writ of habeas corpus was accepted and Sandra was declared a “non-human person”, the first of many attempts around the globe to grant rights to wild animals in captivity. The court ruled that Sandra was a sentient being with thoughts, feelings who has been wrongfully deprived of her freedom, subjected to unjust confinement at the zoo. Sandra has the right to be considered a “subject” of law, rather than a mere object or a “thing”. Claims in the United States, by the Nonhuman Rights Project seeking Habeas Corpus for four privately-owned chimpanzees in New York state have had less clear results.